The Other Side of The Mint

There is more to The Royal Mint than coins. Medal-making has long played an important role at The Royal Mint, linking the organisation with significant moments in national and international history.

There is more to the Royal Mint than coins. Medal making has long played an important role at The Royal Mint, linking the organisation with significant moments in national and international history. In addition, from the early twentieth century The Royal Mint has been responsible for producing official Government seals, including the Great Seal of the Realm, one of the highest symbols of the monarch’s authority.

From left to right: Medal to commemorate the Queen's Golden Jubilee in 2002 (obverse and reverse); The George Cross, a medal awarded for gallantry

Medals

A medal is usually created to reward individual achievements or to commemorate a momentous event. The best medal designers understand this purpose, so their designs are typically very different to those found on a coin. The field of medallic art allows designers greater freedom of expression and has produced inspiring designs, filled with meaning and symbolism.

Medals at The Mint

Large-scale production of medals at The Royal Mint began about 200 years ago. Before this, medals tended to be made, not officially, but as private commissions by Royal Mint engravers.

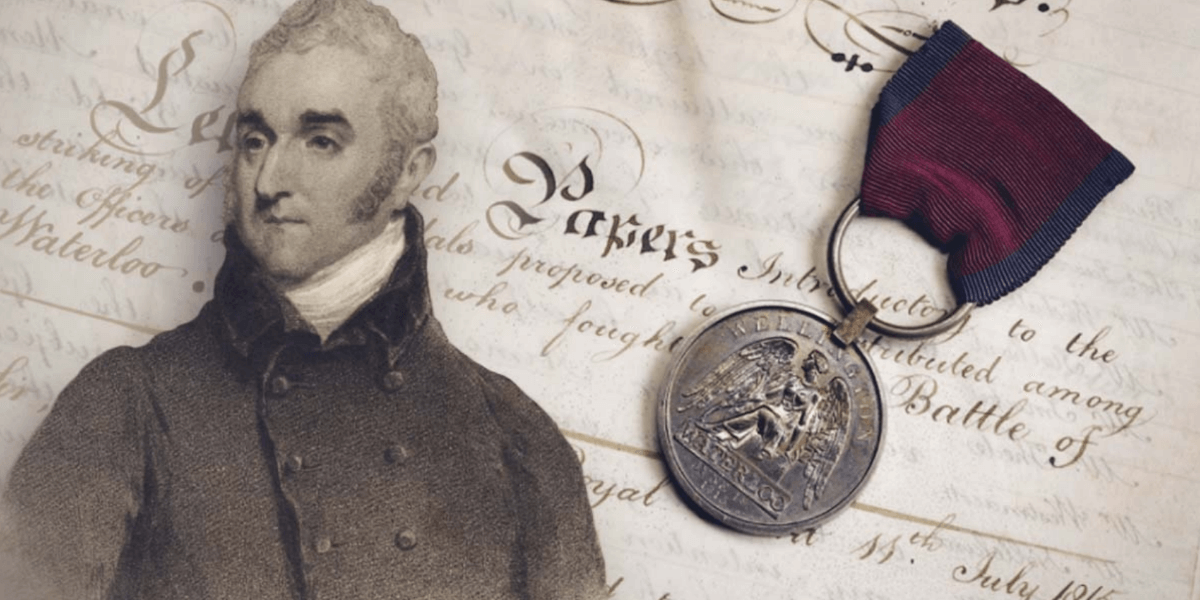

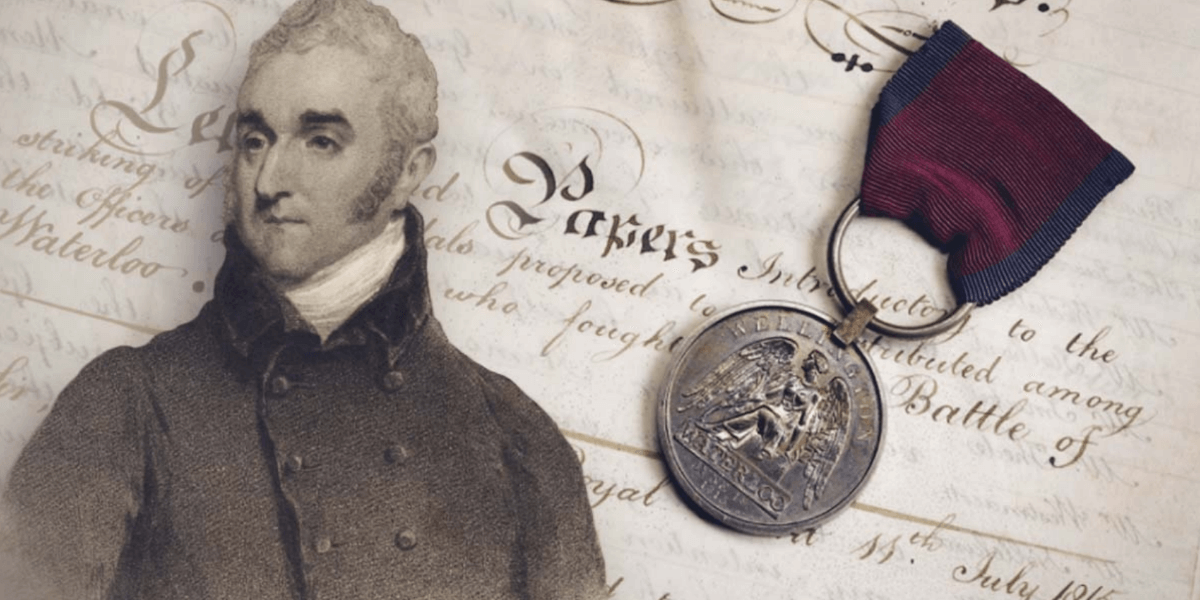

This all changed with the Battle of Waterloo. For the first time, it was decided that every man who fought in the battle should be eligible to receive a campaign medal. At the time the brother of The Duke of Wellington, William Wellesley Pole, was Master of the Mint, so the question of who should produce the medals seemed to have an obvious answer.

From left to right: William Wellesley Pole, Master of the Mint 1814-1823; The Waterloo Medal and the Medal Roll which records the names of all those to whom it was awarded

Making the Waterloo campaign medals was unlike anything The Royal Mint had ever done before. Around 40,000 medals were required and each one had to be individually named.

Pistrucci's Waterloo Medal Dies

Large-scale production of medals at The Royal Mint began about 200 years ago. Before this, medals tended to be made, not officially, but as private commissions by Royal Mint engravers.

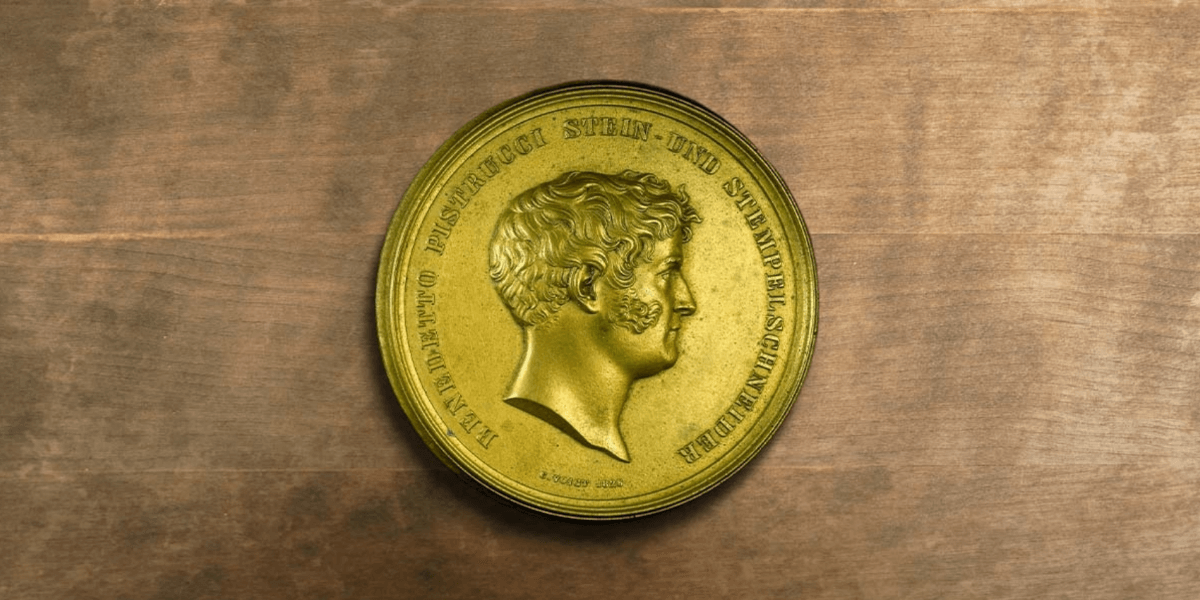

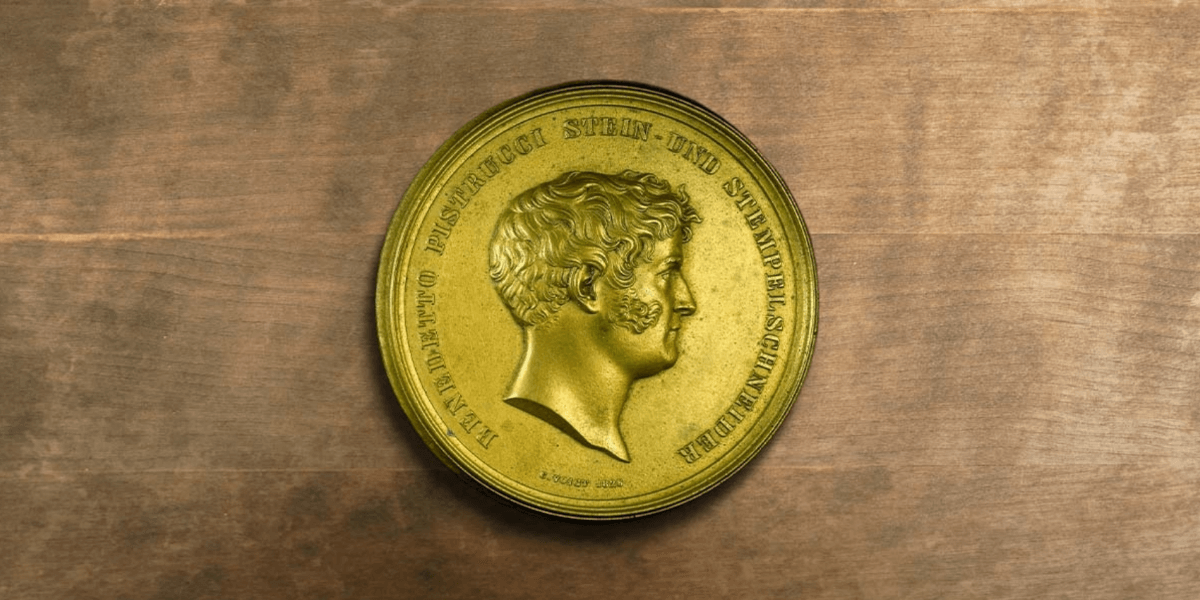

Benedetto Pistrucci’s relationship with The Royal Mint began soon after the Battle of Waterloo. One of the most talented engravers ever to work at the Mint, Pistrucci had a great natural ability, a strong will, and a curiosity for experimenting with new techniques. But he was also very strong minded, sometimes to the point of arrogance which led to conflict with his colleagues.

He was commissioned to create a Waterloo medal to be presented to the Allied leaders and generals who had been victorious over Napoleon.

Medallic portrait of Benedetto Pistrucci by C F Voigt, 1826

It was decided that the medal should be made on the grandest scale, and Pisrucci set about engraving highly intricate designs. But his work was slow and deliberately so. He feared that he had upset and irritated so many of his colleagues that his time at The Royal Mint would come to an end once he handed over the dies. Years passed and eventually, in 1849, Pistrucci was able to hand them over.

In the end, at more than 127 millimetres in diameter, the dies were so large that the risk of hardening them was thought too great and the outcome of a project that had begun 30 years before was that no medals were ever struck.

Pistrucci's Waterloo medal dies

Olympic and Paralympic Medals

Even with a history of over 1,100 years, there is always the opportunity to achieve something for the first time.

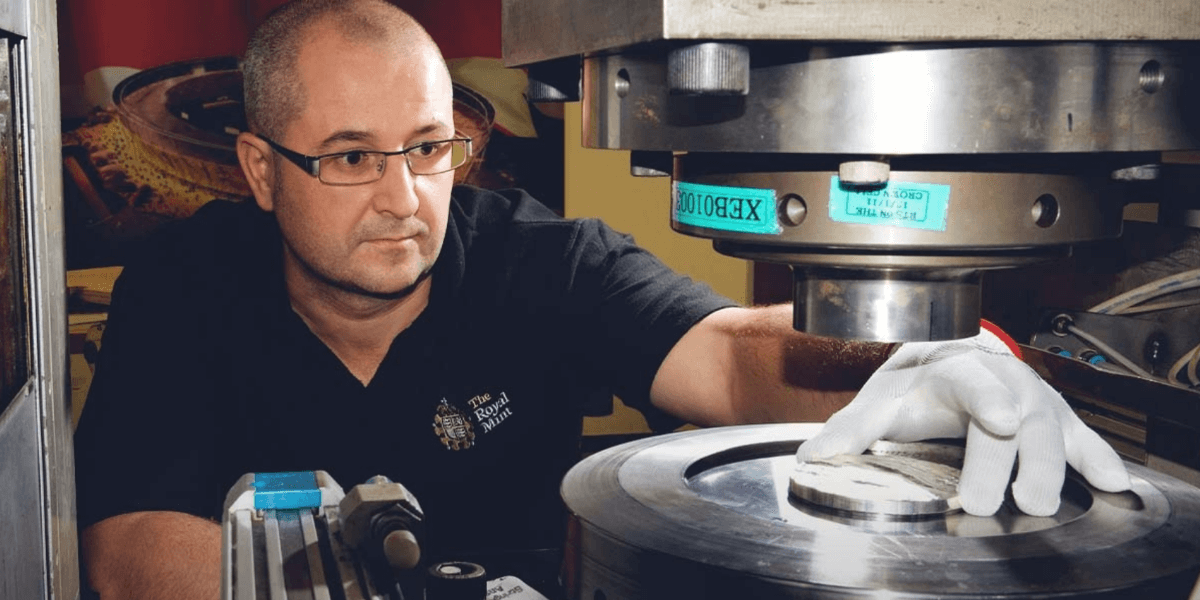

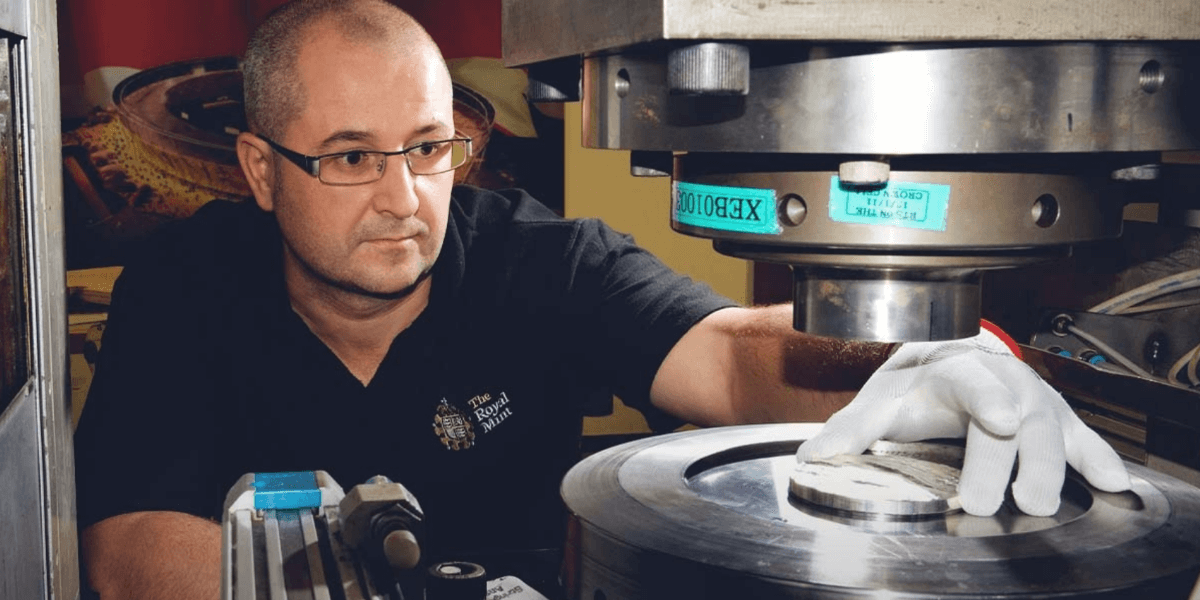

In readiness for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, The Royal Mint struck all 4,700 medals. At over 76 millimetres in diameter they were the largest, and the heaviest, Summer Games medals ever produced. They were so large, in fact, that a new press, nicknamed ‘Colossus’, had to be installed to strike them.

Each medal took ten hours to make with 22 individual processes. It was an incredible achievement and everyone involved felt a huge sense of pride in being part of the Games.

'Colossus' the press used to strike the Olympic medals

The Royal Mint during the First and Second World Wars

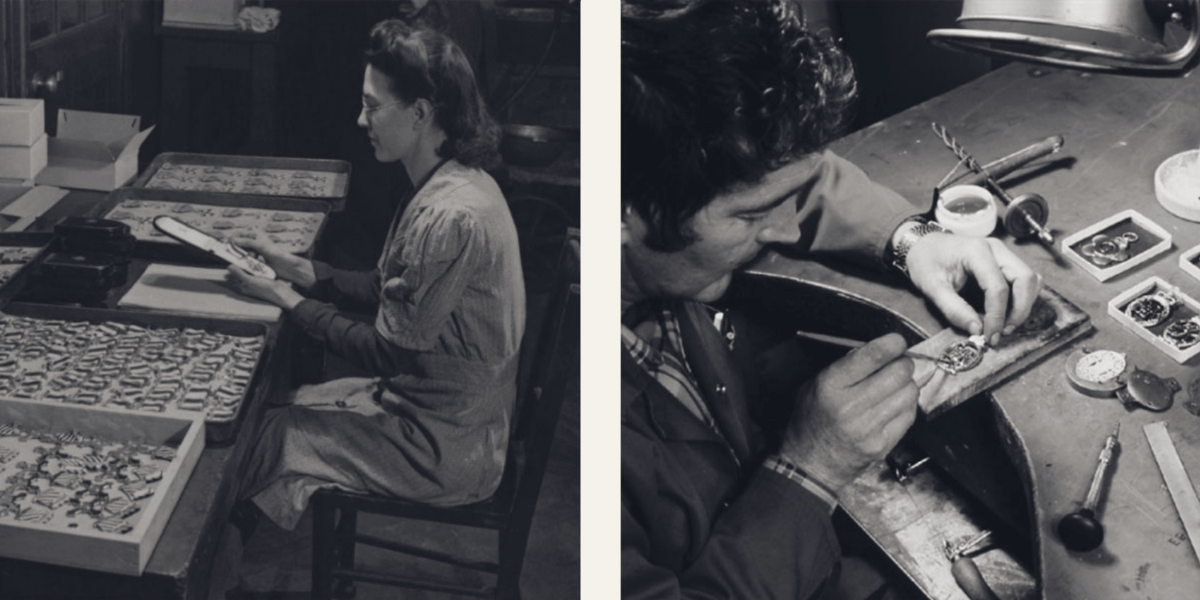

When war was declared in the summer of 1914 The Royal Mint was called upon to play its part, a role it resumed when war was declared for a second time in 1939.

Defence medal 1939-45

The outbreak of the First World War saw heavy demands for coins and medals placed on the Royal Mint. During the years that followed staff worked long hours and William Hocking, a senior figure in the organisation and the first Curator of the Royal Mint Museum, wrote of the ‘converging pressure here for money, medals, munitions and medals’.

Despite the added workload, The Royal Mint also remained responsible for striking medals for the armed forces, with orders for millions of service medals to honour those who had taken part.

The First World War Victory Medal

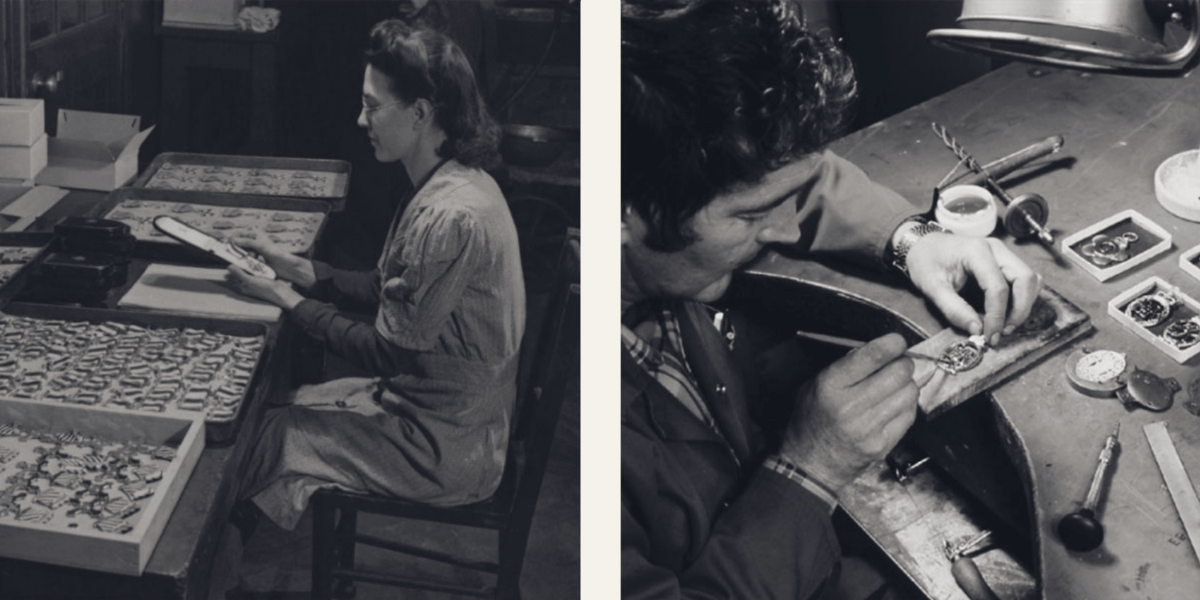

The centuries-old requirement to produce coins as accurately as possible, with skills handed down from generation to generation, had given The Royal Mint a highly talented workforce. During both conflicts this was recognised by the War Office, resulting in requests for assistance with high-precision work, such as making dial sights, gauges and automatic balances to weigh cartridges.

From left to right: Medal packing at Tower Hill; Medal production at Llantrisant

Medals in Wales

Military medals and awards have remained an integral part of the Mint’s production since moving to Llantrisant.

Nearly every major campaign medal for British troops since the 1970s has been struck in Wales, some being made in challenging circumstances. This was the case with the Falklands Campaign Medal which the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, believed should take no longer to design and make than the time taken to assemble the task force to send to the South Atlantic. Instead of allowing the normal time of roughly a year, some 40,000 pieces were struck in the space of a few months.

From left to right: The South Atlantic Medal; Member of the Order of the British Empire medal (female version)

Civil awards for the Fire, Police, Ambulance and Prison services are also manufactured at The Royal Mint, in addition to private prize medals and prestigious royal prize medals.

Seals of the Realm

In 1901 The Royal Mint became responsible for the production of official seals, including the Great Seal of the Realm.

The Great Seal is a monarch’s personal stamp, or signature, and has been used since Anglo-Saxon times to signify approval of important documents.

In times when few people could read or write the Great Seal provided a clear expression of royal authority which was universally understood. Today, The King acts on the advice of the Government, but the Seal remains an important symbol of his role as Head of State.

From left to right: The first Great Seal of Queen Elizabeth II, designed by Gilbert Ledward; Due to Her Late Majesty’s long reign a new seal, designed by the sculptor James Butler, was introduced in 2000. The plaster model for the reverse of the seal is close to one metre in diameter

Content provided, with thanks, by The Royal Mint Museum.

The Other Side of The Mint

There is more to The Royal Mint than coins. Medal-making has long played an important role at The Royal Mint, linking the organisation with significant moments in national and international history.

There is more to the Royal Mint than coins. Medal making has long played an important role at The Royal Mint, linking the organisation with significant moments in national and international history. In addition, from the early twentieth century The Royal Mint has been responsible for producing official Government seals, including the Great Seal of the Realm, one of the highest symbols of the monarch’s authority.

From left to right: Medal to commemorate the Queen's Golden Jubilee in 2002 (obverse and reverse); The George Cross, a medal awarded for gallantry

Medals

A medal is usually created to reward individual achievements or to commemorate a momentous event. The best medal designers understand this purpose, so their designs are typically very different to those found on a coin. The field of medallic art allows designers greater freedom of expression and has produced inspiring designs, filled with meaning and symbolism.

Medals at The Mint

Large-scale production of medals at The Royal Mint began about 200 years ago. Before this, medals tended to be made, not officially, but as private commissions by Royal Mint engravers.

This all changed with the Battle of Waterloo. For the first time, it was decided that every man who fought in the battle should be eligible to receive a campaign medal. At the time the brother of The Duke of Wellington, William Wellesley Pole, was Master of the Mint, so the question of who should produce the medals seemed to have an obvious answer.

From left to right: William Wellesley Pole, Master of the Mint 1814-1823; The Waterloo Medal and the Medal Roll which records the names of all those to whom it was awarded

Making the Waterloo campaign medals was unlike anything The Royal Mint had ever done before. Around 40,000 medals were required and each one had to be individually named.

Pistrucci's Waterloo Medal Dies

Large-scale production of medals at The Royal Mint began about 200 years ago. Before this, medals tended to be made, not officially, but as private commissions by Royal Mint engravers.

Benedetto Pistrucci’s relationship with The Royal Mint began soon after the Battle of Waterloo. One of the most talented engravers ever to work at the Mint, Pistrucci had a great natural ability, a strong will, and a curiosity for experimenting with new techniques. But he was also very strong minded, sometimes to the point of arrogance which led to conflict with his colleagues.

He was commissioned to create a Waterloo medal to be presented to the Allied leaders and generals who had been victorious over Napoleon.

Medallic portrait of Benedetto Pistrucci by C F Voigt, 1826

It was decided that the medal should be made on the grandest scale, and Pisrucci set about engraving highly intricate designs. But his work was slow and deliberately so. He feared that he had upset and irritated so many of his colleagues that his time at The Royal Mint would come to an end once he handed over the dies. Years passed and eventually, in 1849, Pistrucci was able to hand them over.

In the end, at more than 127 millimetres in diameter, the dies were so large that the risk of hardening them was thought too great and the outcome of a project that had begun 30 years before was that no medals were ever struck.

Pistrucci's Waterloo medal dies

Olympic and Paralympic Medals

Even with a history of over 1,100 years, there is always the opportunity to achieve something for the first time.

In readiness for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, The Royal Mint struck all 4,700 medals. At over 76 millimetres in diameter they were the largest, and the heaviest, Summer Games medals ever produced. They were so large, in fact, that a new press, nicknamed ‘Colossus’, had to be installed to strike them.

Each medal took ten hours to make with 22 individual processes. It was an incredible achievement and everyone involved felt a huge sense of pride in being part of the Games.

'Colossus' the press used to strike the Olympic medals

The Royal Mint during the First and Second World Wars

When war was declared in the summer of 1914 The Royal Mint was called upon to play its part, a role it resumed when war was declared for a second time in 1939.

Defence medal 1939-45

The outbreak of the First World War saw heavy demands for coins and medals placed on the Royal Mint. During the years that followed staff worked long hours and William Hocking, a senior figure in the organisation and the first Curator of the Royal Mint Museum, wrote of the ‘converging pressure here for money, medals, munitions and medals’.

Despite the added workload, The Royal Mint also remained responsible for striking medals for the armed forces, with orders for millions of service medals to honour those who had taken part.

The First World War Victory Medal

The centuries-old requirement to produce coins as accurately as possible, with skills handed down from generation to generation, had given The Royal Mint a highly talented workforce. During both conflicts this was recognised by the War Office, resulting in requests for assistance with high-precision work, such as making dial sights, gauges and automatic balances to weigh cartridges.

From left to right: Medal packing at Tower Hill; Medal production at Llantrisant

Medals in Wales

Military medals and awards have remained an integral part of the Mint’s production since moving to Llantrisant.

Nearly every major campaign medal for British troops since the 1970s has been struck in Wales, some being made in challenging circumstances. This was the case with the Falklands Campaign Medal which the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, believed should take no longer to design and make than the time taken to assemble the task force to send to the South Atlantic. Instead of allowing the normal time of roughly a year, some 40,000 pieces were struck in the space of a few months.

From left to right: The South Atlantic Medal; Member of the Order of the British Empire medal (female version)

Civil awards for the Fire, Police, Ambulance and Prison services are also manufactured at The Royal Mint, in addition to private prize medals and prestigious royal prize medals.

Seals of the Realm

In 1901 The Royal Mint became responsible for the production of official seals, including the Great Seal of the Realm.

The Great Seal is a monarch’s personal stamp, or signature, and has been used since Anglo-Saxon times to signify approval of important documents.

In times when few people could read or write the Great Seal provided a clear expression of royal authority which was universally understood. Today, The King acts on the advice of the Government, but the Seal remains an important symbol of his role as Head of State.

From left to right: The first Great Seal of Queen Elizabeth II, designed by Gilbert Ledward; Due to Her Late Majesty’s long reign a new seal, designed by the sculptor James Butler, was introduced in 2000. The plaster model for the reverse of the seal is close to one metre in diameter

Content provided, with thanks, by The Royal Mint Museum.